Metal ages

Chalcolithic Age (5000 BCE to 3000 BCE)

The metal ages started with the discovery of copper. Around 5000 BCE, the Mesopotamians (those that lived in the fertile crescent) started using it in an organised manner - to make tools, and now, weapons too. So we make sickles, knives, and other decorative art items - art was very important back in the day. This period is called the chalcolithic period (chalcos = copper, lithos = stone) because copper and stone were both materials of choice. One reason for the rapid use of copper was that it was much easier to shape and mould than stone.

But there was one problem. Tools made of copper bent rather easily, so many customers returned them, of course, so long as they were within the warranty period. The high volume of returns caused great stress to the early industrialists, so they started looking for a way to solve the problem.

Bronze Age (3000 BCE to 1000 BCE)

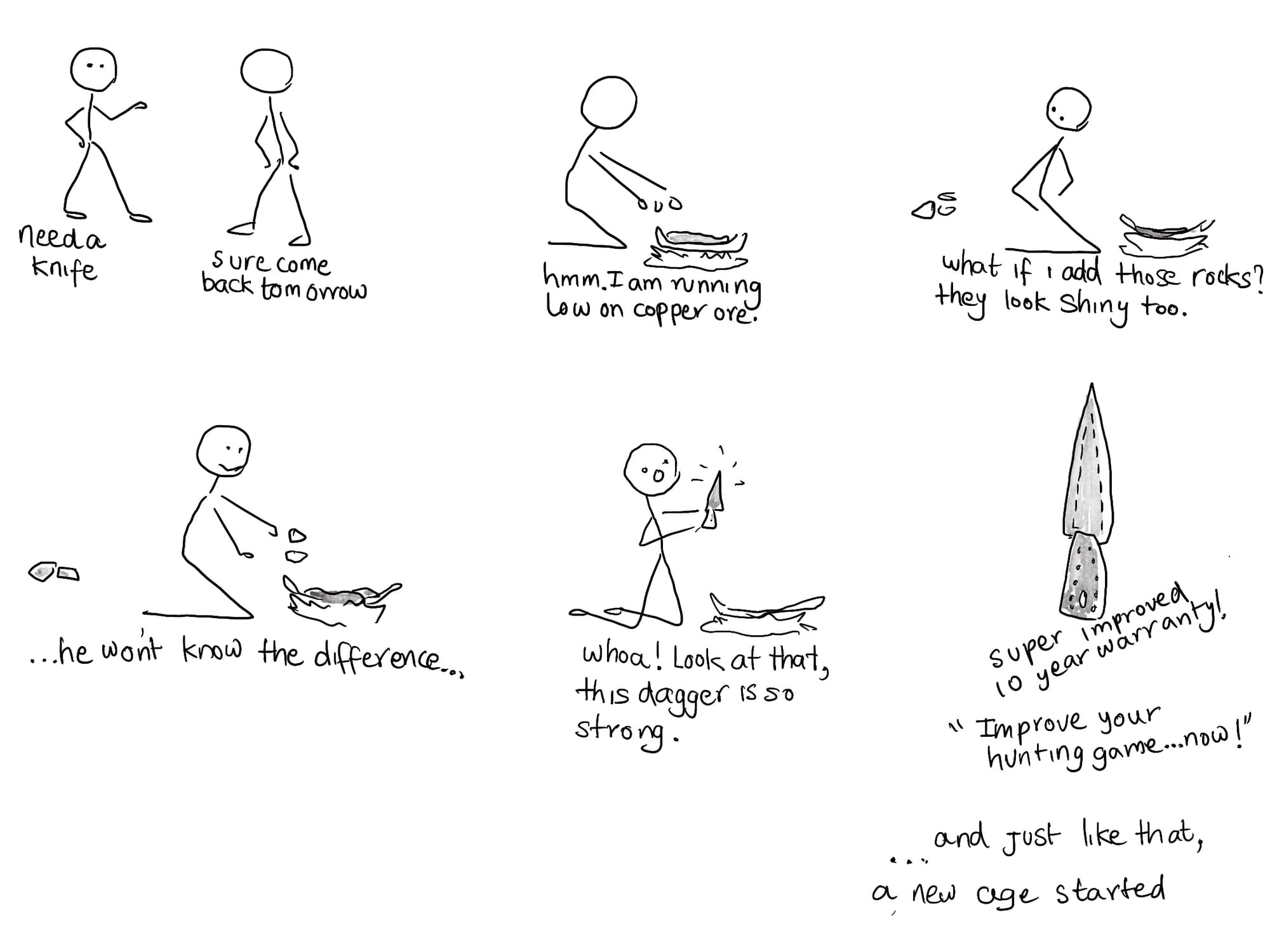

![]()

A likely apocryphal story.

When a little bit of tin is added to copper, the alloy formed is stronger than either tin or copper used separately. Yes, this is amazing, but chemistry is like that. The new alloy we called Bronze became so popular that it had its own age named after it.

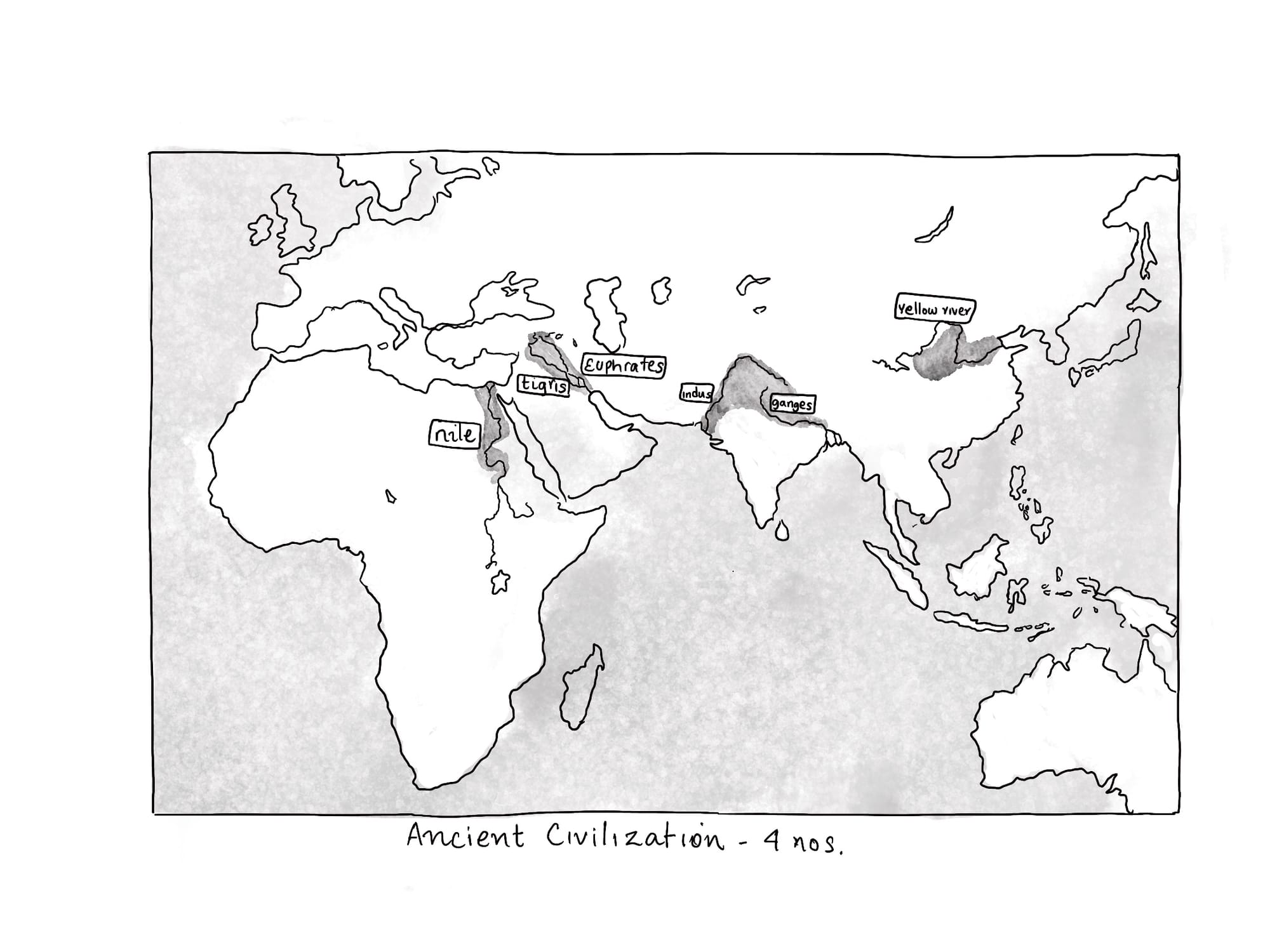

By now, there were four major civilisations in the world, and they all benefitted from the use of stone, copper, and bronze.

- Ancient Egypt Civilisation.

- Mesopotamia and Babylonia Civilisation.

- Harappan and Vedic Civilisation.

- Shang Civilisation.

The early years of this age were a time of great prosperity. Farming was great. Metal making was great. What else could one want?

All of them lasted about 500 years (Indus lasted a bit longer, about 800 years). Eventually, they all fell due to war, famine, climate change, overpopulation, and war (did I say that already?). But for now, let's rewind to the good times and see how people lived in one of those civilisations: The Indus Valley Civilisation.

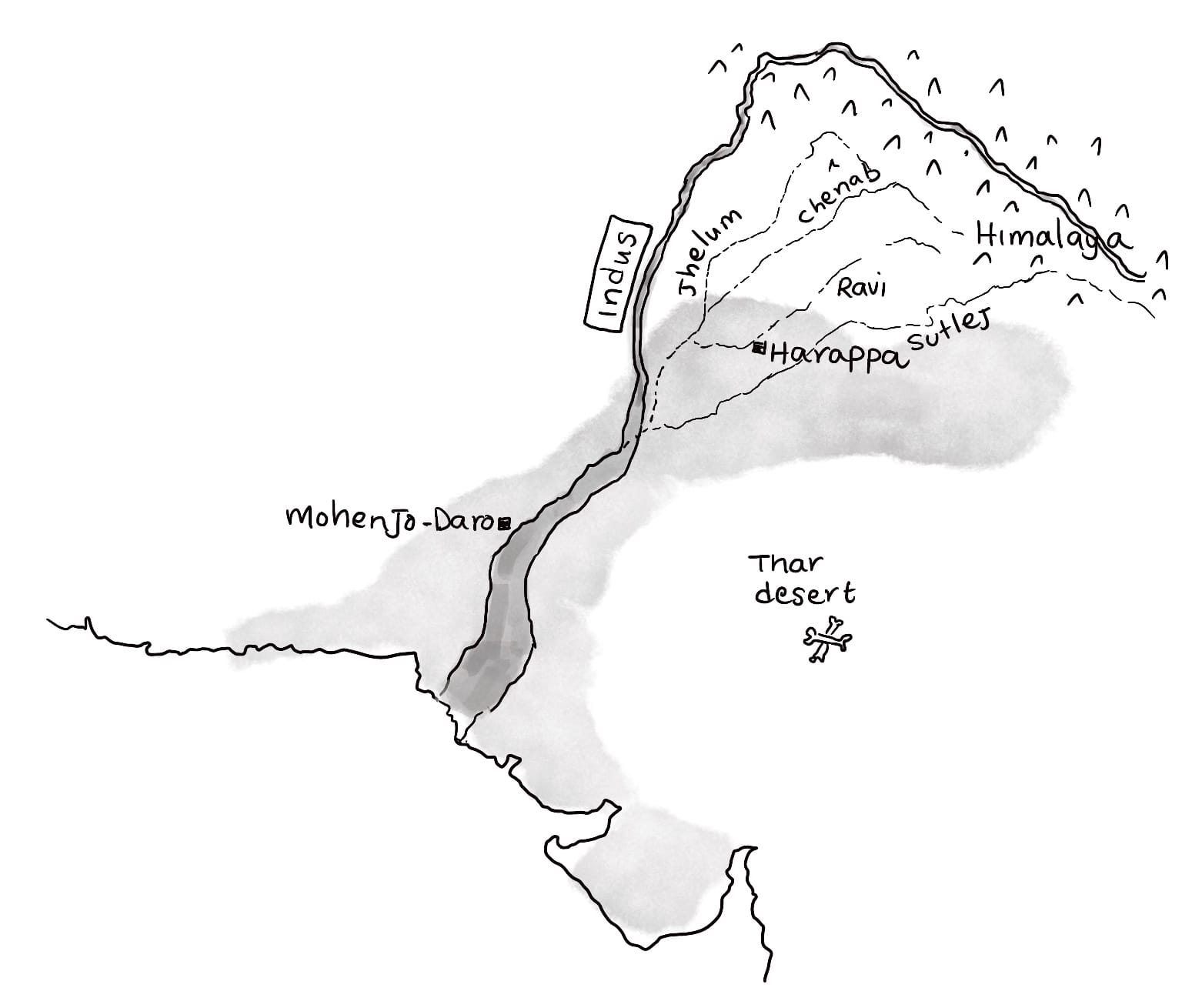

Indus Valley Civilisation (3000 BCE to 1300 BCE)

About 2600 BCE, a river valley civilisation existed just north and slightly to the west of modern-day India. If you reached Afghanistan, turn back as you went too far. Here flows the mighty Indus river, as it did 5000 years ago. What initially started as a small band of farmers grew into a village, a town, and eventually into one of the biggest cities in the world. These were the twin cities of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa.

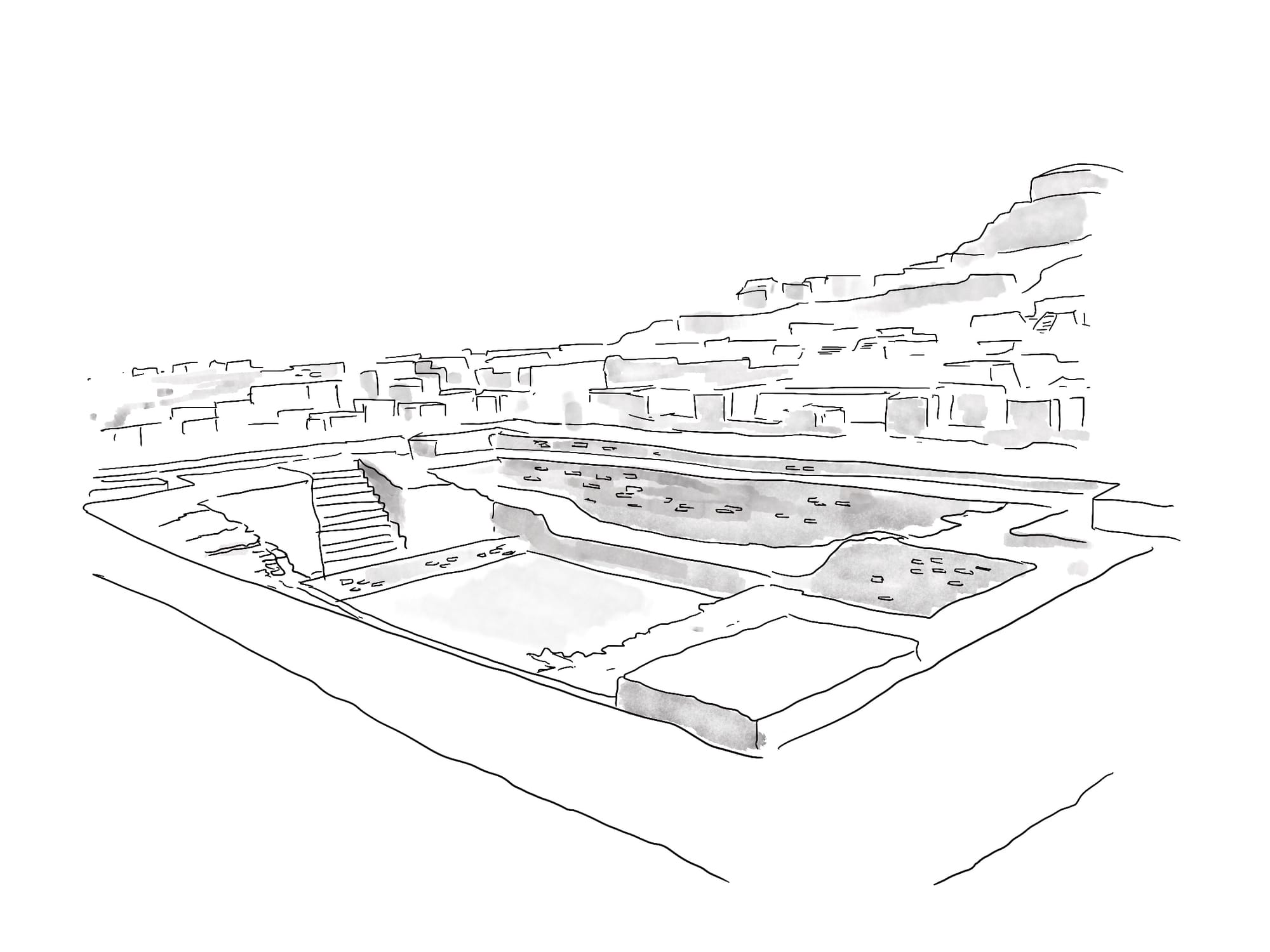

When archaeologists discovered the city's remains, they were surprised at the scale of development. This was far more evolved than a simplistic neolithic settlement. They had houses, some of them even two or three storeys high. They had a centralised bath (swimming pool for the rich), a very efficient system of draining waste water, and workshops that made pottery and copper tools (it was the copper age, after all).

The great bath that many would have gone to after a hard day of pottery making.

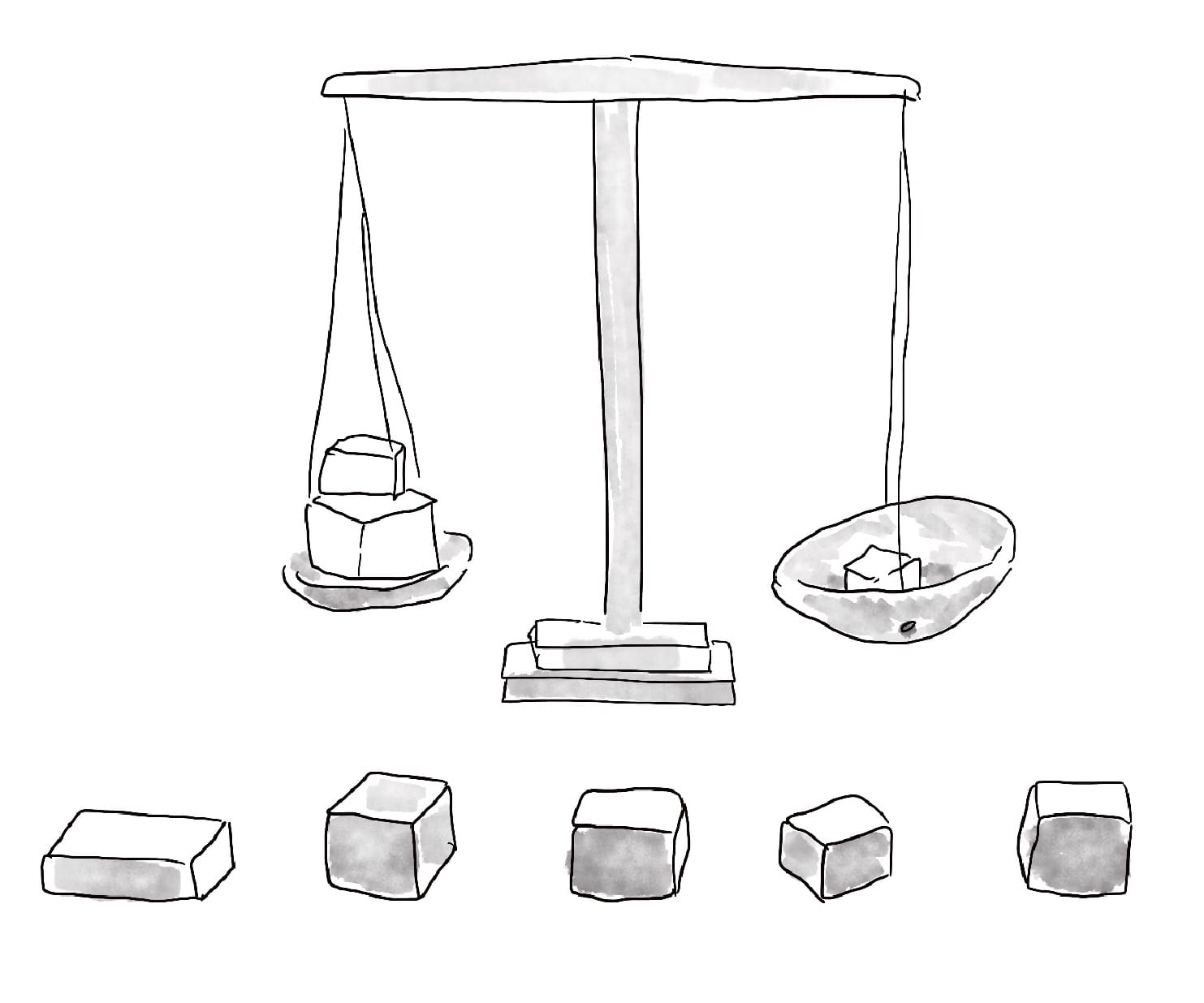

Cubical weights in graduated sizes. The weights used a binary weight system long before they were made popular by computers. As the weights grew larger, they switched to the decimal system.

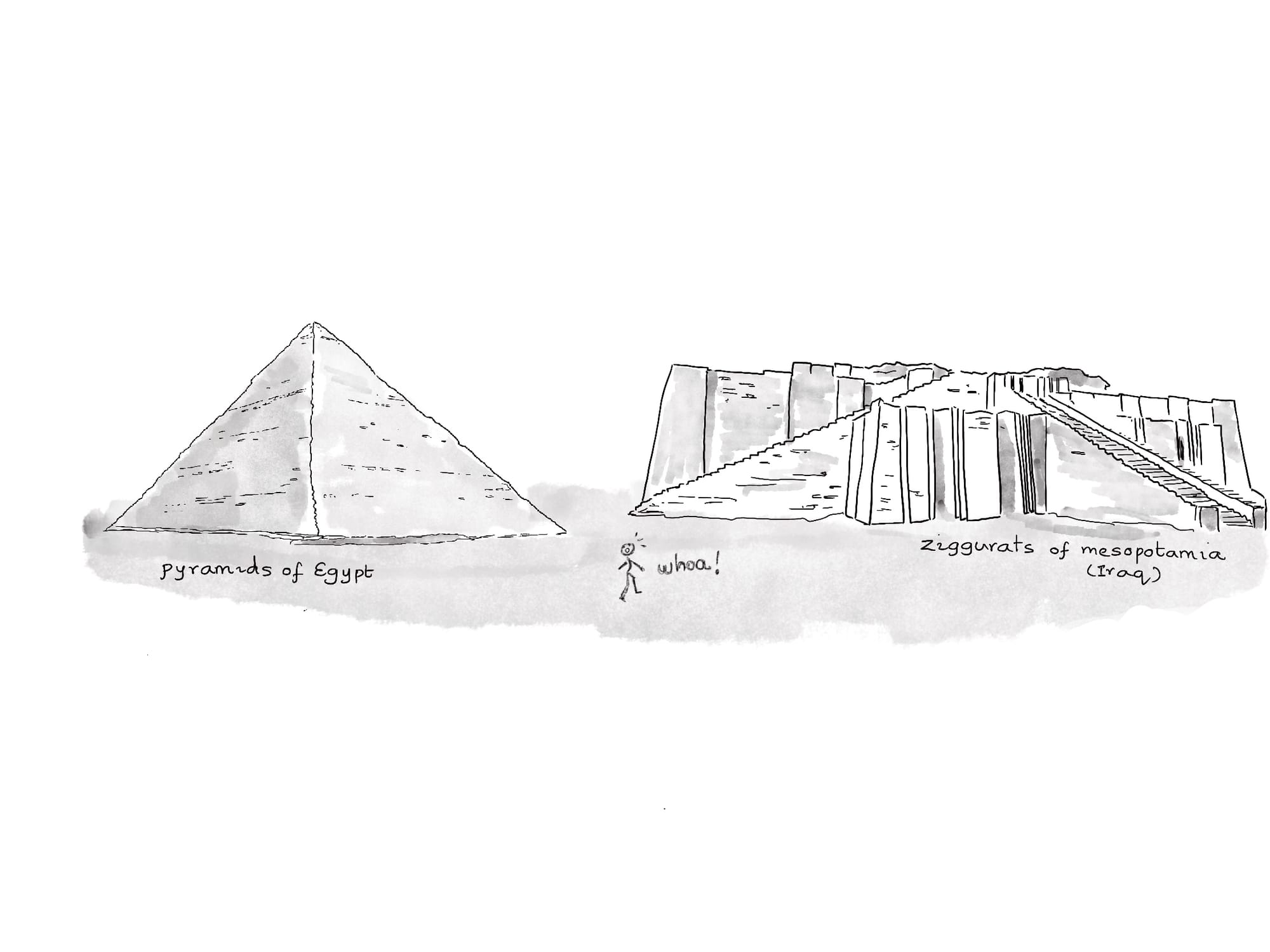

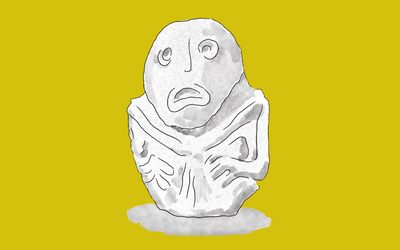

It's hard to build a city without some form of governance. So what kind of government did these people have? The answer may lie in how different the artefacts are from those excavated in Egypt and Mesopotamia - two places that also had a thriving civilisation at the same time. In Egypt and Mesopotamia, the excavations led to very grandiose findings, such as the pyramids in Egypt or the ziggurats in Mesopotamia.

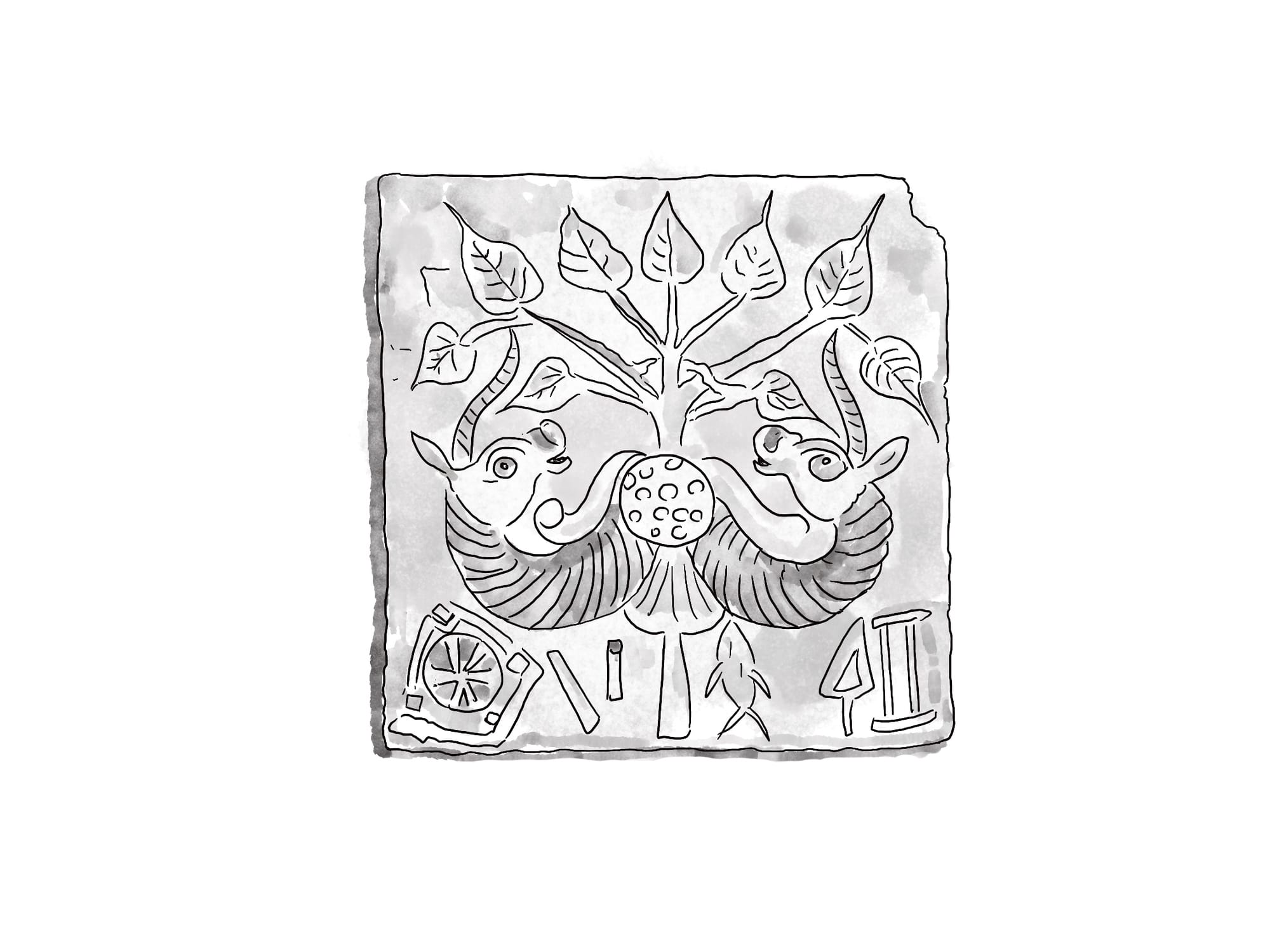

However, everything we found in the Indus Valley civilisation was much more modest and practical. For example, we found seals and lots of them. How were they used? Well, mostly for trading with the other two civilisations. Of course, the seller could not go himself, so he would basically Dunzo it through a third party, making sure to seal his goods before handing them over to the courier. The buyer (in Mesopotamia or Egypt) would check the seal before accepting the goods. We know this because seals from the Indus Valley civilisation have appeared in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

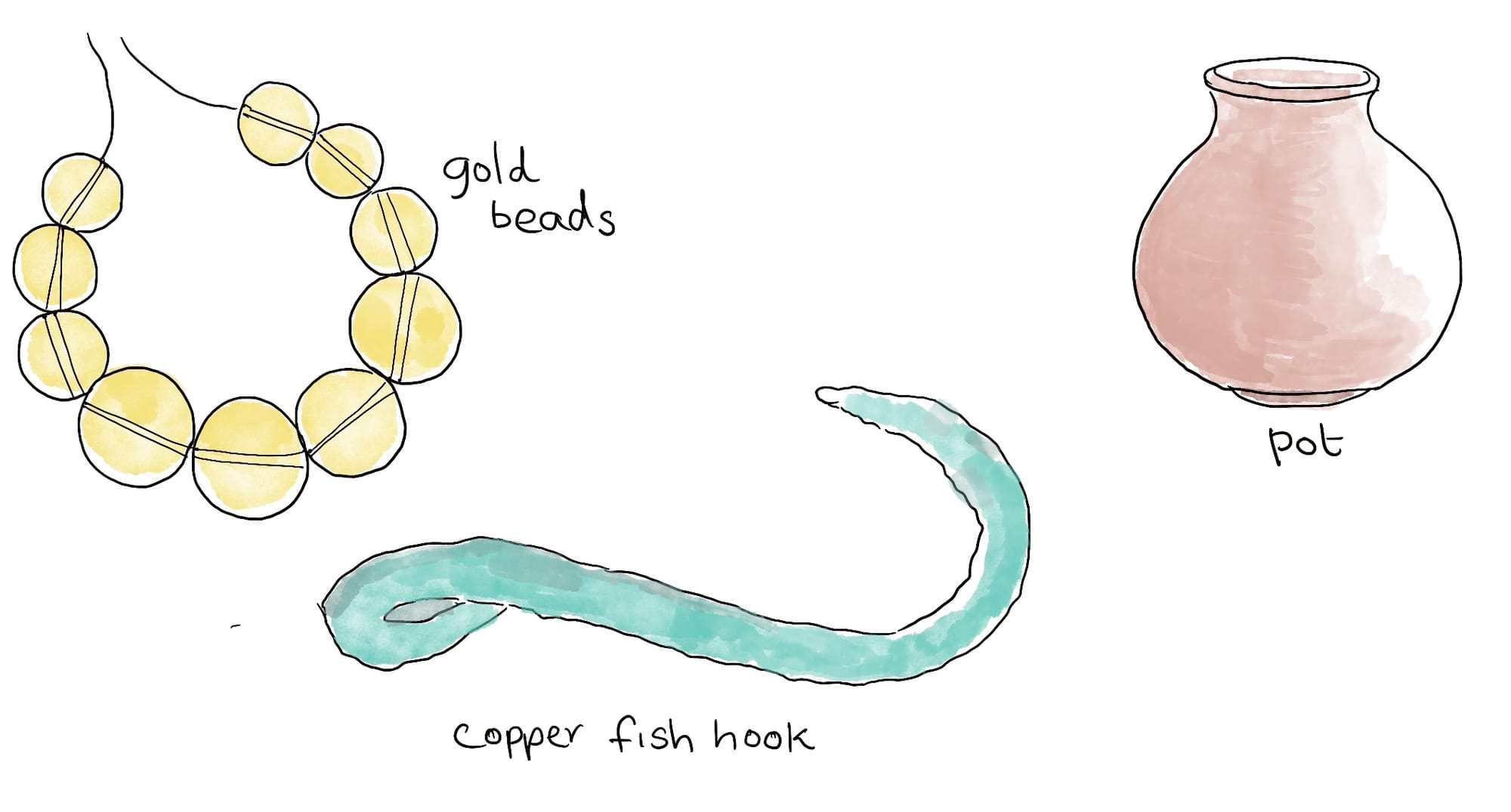

Like the one above, Seals usually had some animal, mythical or actual, and some markings to identify the trader. Here are some other simple objects.

No pyramids, ziggurats, or great sculptures depicting warfare.

Why?

One explanation is that the people here were dull and lazy. Some historians believe that. But how did this dull population create such an elaborate set of roads and drains, dig hundreds of wells, make exquisite pottery and trade with the other two civilisations effortlessly?

The other theory is that the two cities were not ruled by god-like kings but by a group of people that represented the society. Of course, you would build grand things if the king funded you which would often be to sing his praise or His praise. Conversely, if he did not, you would build it for yourself. That may explain why there were no pyramids in Indus Valley and no grand palaces. Or religious artefacts.

A government not based on religion, without a king, is run by a group from every stratum of society. Sounds familiar? It may have been a representative democracy. A republic. The first republic.

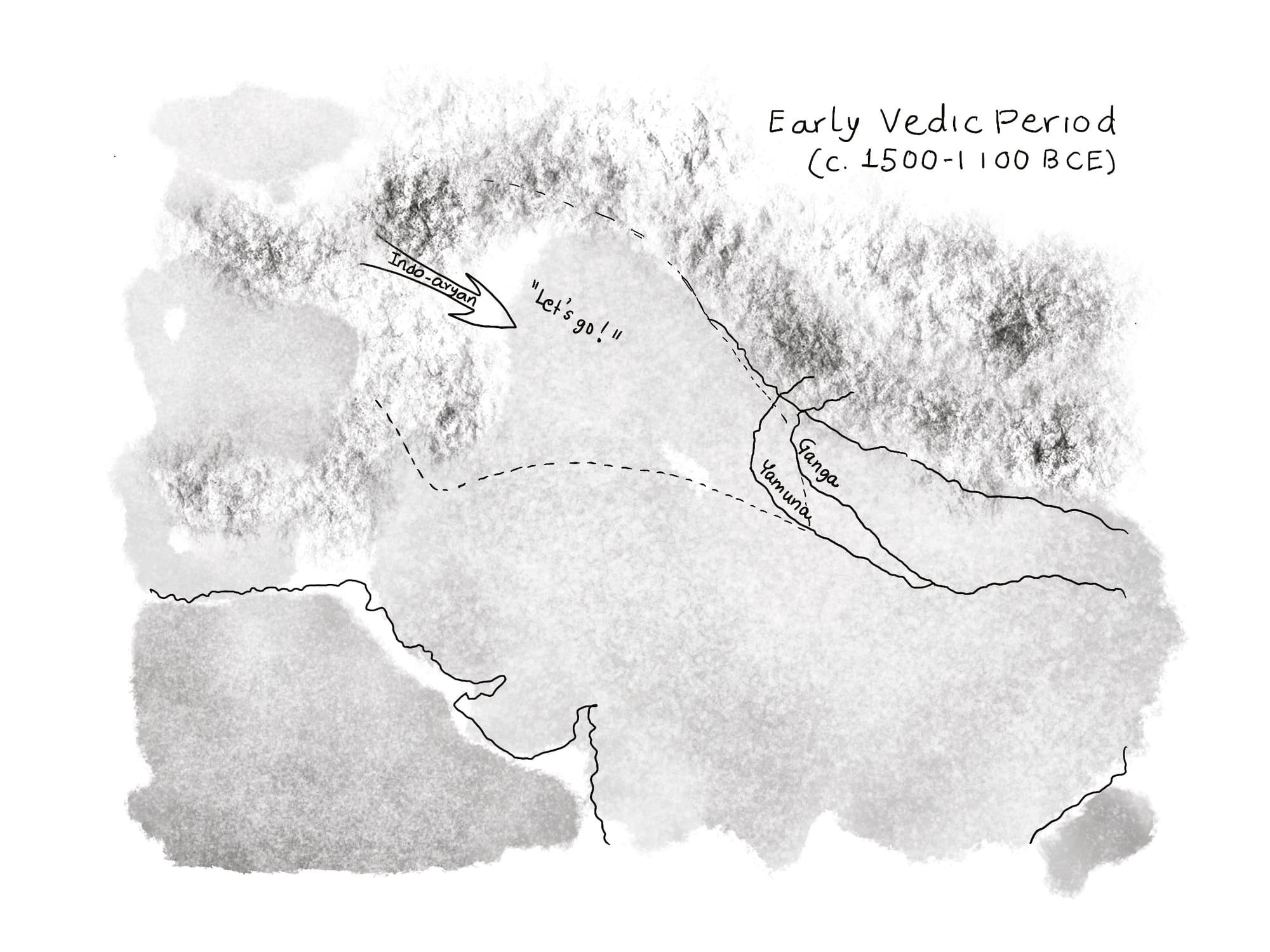

It lasted for 700 years, but eventually, it perished due to overpopulation and a protracted era of drought that led to the drying up of rivers. Overpopulation may have also been due to the arrival of a new set of people from Central Asia, the Aryans, who reached this land and settled down with the rest of the existing inhabitants. It was as a visa on arrival to the Aryans.

The Vedic Period

Towards the end of the Indus Valley Civilisation, we see the first evidence of "written wisdom" in the Rig Veda, one of the earliest "books" in the world. Of course, this was all written by hand, so there were few to pass around. It was all by word of mouth. But we had come a long way from the Australopithecus Afarensis, as you can make out by one of the parts of the Rig Veda, translated to English from the original language Sanskrit it was written in.

There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

Neither the realm of space, nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?

There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That One breathed, windless, by its own impulse;

Other than that there was nothing beyond.

Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That One by force of heat came into being;

Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

Gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?

Whether God's will created it, or whether He was mute;

Perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not;

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

Only He knows, or perhaps He does not know.

Rigveda 10.129 (Abridged, Tr: Kramer / Christian)

Around 1500BCE, people had to abandon the region and move on south. They went back to the countryside to become farmers again. Thus came the end of one of the great ancient river valley civilisations.

Of course, those small villages then banded up together again and, in a few hundred years, found themselves in towns next to another great river - river Ganga. The Aryans that arrived here quickly named it Aryavarta (should someone else lay claim to the land).

By about 1000 BCE, small kingdoms called Janapadas would form here. The initial ones echoed the republican nature of the Indus government, but monarchy was now knocking at the doors.

And a new heavy metal age was coming too. The iron age. With apologies to fans of Iron Maiden.

Iron Age (1000 BCE to now)

![]()

Around 1000 BCE, most of the world turned to iron, from bronze, as the preferred metal to make nails, hammers, spears and daggers. Iron was not as good a metal as bronze. But iron was plentiful and, therefore, cheaper to make. And tin was getting harder to get by as wars had broken off in Mesopotamia, affecting tin shipments.

Most people were farmers because it was the easiest way to make a livelihood; the land was fertile, and the tools were cheaper and better. The quality of life increased rapidly. Houses and villages came up as societies grew more common.

With the bronze age, people had settled down in one place for most of their lives. With the iron age, they now wanted to ensure the next generations could live there too. So it became essential to own and pass ownership of land.

500 hundred years later, around 500 BCE, a man called Herodotus came along. He started writing down the affairs of his times. The age of pre-history was over, and the age of history started.

Note: The Chinese would disagree, as their written history started much before Herodotus, but global relations were not so good back then, as they are not even now - so there's debate on who is the first historian.

When did the Iron age end? Well, look around. It's still going on.