Make a LED blink

Make a LED blink

I would not take a second shock for the kingdom of France - Ewald Georg von Kleist

A shocking discovery

A capacitor is one of the basic building blocks of most electronics circuits. But what exactly is a capacitor, and how did it come to be? To answer that question, we need to get into our time machine and set the dial to…about 1650…that’s about 350 years ago!

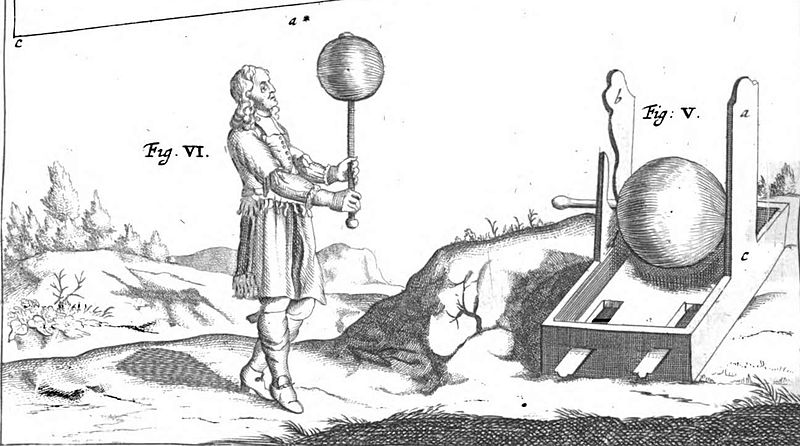

Here is Otto Gericke from Germany, having just completed a remarkable experiment. He rotates a ball of sulphur by means of a crank, and then when he touches the rotating ball with a pad, an “electrical” spark occurs. He does not know it quite yet, but what he’s done is create the first electric generator based on just “friction”.

About a 100 years later, in 1744, another German called Ewald Georg von Kleist with a mouthful of a name, tries to accumulate this “electric” charge into a jar because it’s common knowledge at the time that this electricity thing is some sort of “fluid”. So with some clever thinking he connects the electric generator aka the “friction” machine to a jar filled with water using a piece of metal bar and metal chains. But while holding the jar, he touches the metal chain that dips into the water…and is thrown clear across the room. He later on comments that, “I would not take a second shock for the kingdom of France”. In fact, he and his associates are loathe to repeat the experiment again, yet they tell all their fellow experimenters exactly what they did…and never to try and repeat.

Well repeat they did! News about the experiment reached a person named Andreas Cuneaus who is shown below, conducting the same experiment again with Professor Peter van Musschenbroek (possibly the person on the right), and sure enough, when he touched the wire dipping into the water while holding the jar - zppfft - a shock again!

Despite the painful shocks, the experimentars at the time had succeeded in their original objective - to store “electricity” and then use it at will. And what was their will? Well to begin with - to gather a bunch of rich folks in a room, and show a spark of electricity, that was bound to get a lot of the oohs and aahs! Some also used it to administer shock to patients suffering from one condition or the other…and so on.

Understanding the capacitor

So this brings us to the question - why the shock? Well, the excess charge formed due to the friction had transferred all the way across to the glass of the jar (and not to the water as expected). The glass now had excess negative charge, and the wire held positive charge (or absence of negative charge). There was now a voltage difference between the two areas, and when Andreas touched them both, electricity flowed through his body (since the human body is a conductor as well) causing the shock!

It was later on left to Benjamin Franklin and Michael Faraday to work out the physics behind the “Leyden” jar, as it was now called after the professor of Leyden who experimented with it. They were able to understand that the charges lay not in water, but in the glass and the wire, and the water itself was acting as an “insulator” to keep the charges apart. They built better versions the jar that looked nothing like the jar itself - flat, and all glass, and with variable charge. The “jar” was then renamed to “condenser” since it was a formed of “condensed electricity”, and even later on it was given its current name - the capacitor. In honour of Michael Faraday, the unit of capacitance is a “farad” and it now capacitors look this!

Despite their appearance, they all function the same way - storing some amount of charge, and discharging in a “flash”!

Uses of a capacitor

The main use of the capacitor 300 years ago was to somehow store some electrical charge so that experiments could be performed at a later time. In fact, it was Benjamin Franklin that connected a bunch of “Leyden” jars togethers and called them a battery similar to a “battery of canons”.

Remember that the battery we see today hadn’t been invented yet. So the capacitor can be thought of as the ancestor to today’s battery.

Once the battery as we know it today was discovered, the Leyden jar (or capacitor as we know it today) was quickly discarded. The chemical reaction in a battery is able to product sufficient electrical current over a much longer period of time than the capacitor. If not as a battery, then what other purpose does a capacitor serve then?

Well, the ability for a capacitor to store a lot of charge, and discharge all of it in a flash can be used in…a flash. That’s how a flash in a camera actually works. Capacitors can also be used to block the passage of direct currents in a circuit. The ability for a capacitor to charge and discharge can also be used to create circuits that “oscillate” between two states. So as you can see, the capacitor is a kind of joker in the pack, able to to do multiple things. In this experiment, we will create a simple blinking LED (on-off-on-0ff and so on) using a capacitor and another component called a relay.

But let’s not just talk about it, let’s make it!

What we will make

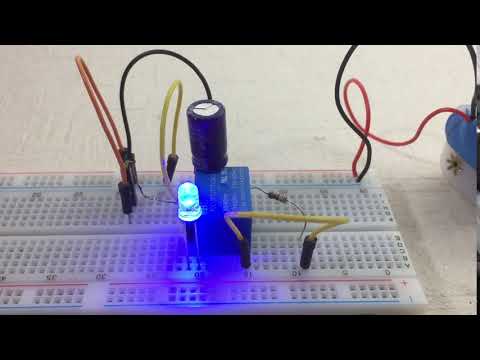

Here’s what it looks like when it’s all done.

Click here to play the above video

Perhaps you could reuse this circuit on top a toy ambulance.

Safety precautions

Relays can be used with higher voltages, but you must not use them with anything higher than 5 volts if you want to remain safe and in one piece.

Things we need

- A LED to blink. Pick a color, your favourite color.

- ~5 volt battery

- 22 ohm resistor

- An electromechanical relay

- One 1000 micro farad capacitor

- Breadboard to place all the electronics components on to test the circuit

- Your toolbox

The blinking LED

This is the circuit we will make on the breadboard.

The green lines cause the capacitor to charge and discharge periodically (we will see more on how this happens shortly but for now, let’s build the circuit on a breadboard starting with the parts in green).

Steps

Step 1: Prepare the common (CO) terminal

The circuit uses an electromechanical relay with five terminals, one of which is the CO (common) terminal. If you are able to place all five pins of the relay properly on the breadboard, then you can skip this step. Usually, that will not be the case, and one of the terminals will not align up correctly. In such a case, solder the CO terminal pin as shown below. Now you should be able to place all 5 pins of the relay on the breadboard.

Step 2: Connect the CO terminal

Connect the positive end of the battery to the CO terminal as shown below.

Step 3: Connect the NC terminal

Connect the NC (normally closed) terminal to a resistor and then connect the other end of the resistor to one of the coil terminals.

Step 4: Place the capacitor

Place the capacitor in parallel with the coil terminals shown below. Note the +ve end (anode, longer pin) is connected to the resistor. The -ve end (cathode, shorter pin) is then connected to the other coil terminal.

Step 5: Complete the green circuit.

Connect the -ve terminal of the capacitor to the -ve terminal of the battery to complete the circuit. (Black jumper in the image below).

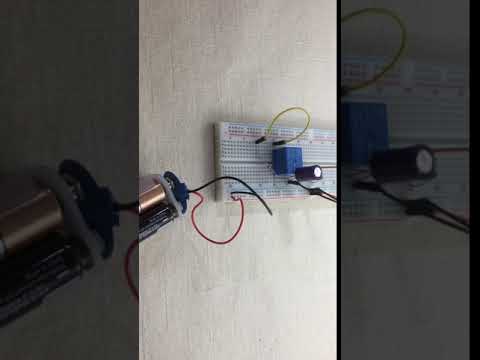

Now provide power to the circuit. You should immediately hear continuous clicking sounds as the switch inside the relay goes on-off-on-off-on-off…

If you do not hear this sound, then go back and redo all the connections. Do NOT move to the next step till you hear clicking sounds.

Click here to play the above video

Step 6: Connect the LED.

Connect the LED’s positive end (anode, longer pin) to the normally open (NO) terminal. Connect the other end of the LED to the -ve end of the battery to complete this circuit.

Note: Depending on the type of LED you may or may not need to add a LED-protecting resistor. In the picture below, the blue LED happens to have enough internal resistance in order to limit the amount of current flow, so the LED does NOT get damaged even when connected directly without a current limiting resistor.

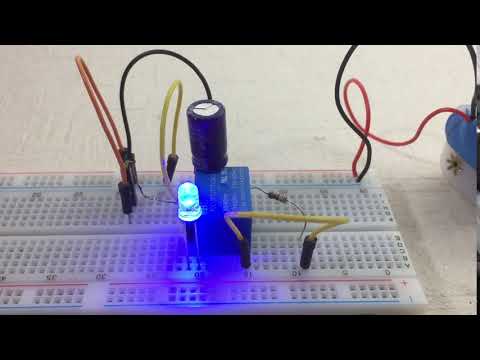

Step 7: Blink!

Finally, we are ready to blink the LED. Power the circuit and if all goes well, you should see a blinking LED.

Click here to play the above video

How does it work?

Refer to the circuit diagram below:

When the battery is connected to the circuit, current starts flowing through the “green” circuit shown above and through coil inside the relay, instantly turning it into an electromagnet. Once that happens, the switch flips and closes the “blue” circuit. But as soon as that happens, the current flow stops because the battery is removed from the circuit, the coil is de-energised and the switch falls back to its original position. And the process repeats itself all over again - the switch “switches” between the two positions continuously and very, very quickly. The speed of electricity, after all, is close to the speed of light itself.

Now, what happens when we place a capacitor in parallel to the coil? It gets charged very quickly as well, but as soon as switch cuts over to the blue circuit, it finds a way to discharge itself via the coil, thereby keeping the coil in the energised state for a bit longer, even when the main battery is disconnected. Holding the coil in the energised state for a fraction of a second longer, causes sufficient number of electrons to flow during that time in the “blue” circuit…causing the LED to glow!

Once the capacitor has discharged all its charge through the coil, the coil goes back to its de-energised state, and the switch cuts off the “blue” circuit now, and the LED stops glowing.

This repeats continuously giving the impression of a “blinking” LED.

Parting thoughts

When the capacitor is blinking connect a multimeter to the two terminals of the capacitor. What value do you see, and why? How can you control the speed at which the LED blinks?